Undefended evictions, barriers to justice and the worrying impact of legal aid crisis in housing

Is a shortage of legal aid solicitors adding to Scotland’s homelessness crisis? Focusing on eviction cases, the University of Glasgow’s Fiona McPhail presents a snapshot of recent data and highlights the true value of this work.

Housing law is an area where the demand for legal services far outweighs the supply of solicitors available. Before joining the University of Glasgow’s Open Justice Centre as a lecturer in social justice I was principal solicitor at Shelter Scotland. Throughout my time at the charity I regularly had to turn people away on the basis that we did not have the capacity to assist them.

This work, unsurprisingly, is mainly legally aided where tenants and homeless people are concerned. Many aspects of housing law will fall within the scope of legal aid and many people in housing crisis will have a legal remedy available to them. Scotland has legislated to strengthen the rights of tenants across both the social and private rented sector in relation to eviction and done similar in relation to homeowners at risk of having their home repossessed.

We often hear about Scotland’s world-leading homelessness legislation, where, with few exceptions, any person who is homeless should be provided, at a minimum, with temporary accommodation. The greatest barrier to access to justice for tenants and homeless people in Scotland right now isn’t a deficit of legally enforceable rights but rather a shortage in solicitors able to defend or enforce those rights.

A need for numbers

In its response to the Equalities, Human Rights and Civil Justice Committee’s Legal Aid Inquiry, the Scottish Legal Aid Board (SLAB) points to the lack of system-wide data on unmet legal need as a weakness of the current system. Without this data, it is unable to target interventions where there is unmet need.

In its statistical report published in April 2025, the Scottish Courts and Tribunals Service (SCTS) reported a 21% increase in proceedings for recovery of heritable property being initiated, from 4,179 in 2023/24 to a projected 5,072 in 2024/25 (SCTS Courts Data Scotland: Civil). The number of mortgage repossessions has also increased (by 29%) and is back to pre-pandemic levels. The statistical report from the First-tier Tribunal for Scotland Housing and Property Chamber (HPC) for 2022/23 records an 80% increase in applications for eviction since 2019/20 (Summary of Work of the HPC 2022/23).

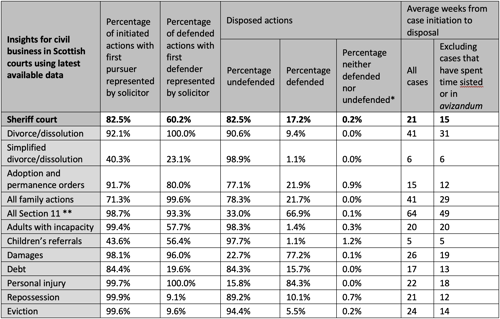

Alongside these figures for the number of actions raised is the following information about legal representation in the sheriff court.

The aforementioned HPC report records that in 2022/23 around 60% of landlords were represented in applications for eviction, in contrast to 7% of tenants. The use of representation may not be a reference to legal representation in the tribunal, as lay representation is permitted. It is however common for landlords to be legally represented and legal aid is available to those who are eligible.

The big picture

The above raw data, even if we allow for a margin of error, paints a picture where equality of arms is far from the norm in the context of eviction proceedings where a household is at risk of losing its home. This is against the backdrop of a national housing emergency where several local authority homelessness services are at risk of systematic failure, struggling to comply with their statutory duties to the homeless.

In fairness to SLAB, it does run several grant-funded programmes that provide legal advice and representation to tenants and homeowners. However, these programmes are restricted to certain sheriffdoms and/or certain types of cases (eg rent arrears) and, most significantly, are funded for 12 months at a time. An annual grant provides little comfort by way of job security or business sustainability. And while we hear a lot about the uncapped judicare budget, the grant-funding budget has decreased over the years. It currently sits at £2.3 million, which is used to fund 17 different services.

On my reading of the Legal Aid (Scotland) Act 1986, and Section 4A in particular, I can’t see there being any legal barriers to expanding the existing programmes in size or scope or indeed launching new programmes to respond to emerging trends in unmet legal need.

SLAB’s own data on expenditure in housing cases under judicare makes for some interesting reading. In 2023/24 there were 622 applications for civil legal aid and 393 grants of civil legal aid under the category of ‘housing/recovery of heritable property’ (SLAB Annual Report 2023/24, Appendix 2). There is no separate data for mortgage repossessions and so it is unclear whether these cases are captured in the 393 grants or fall under the category of ‘other’.

In the same year, SLAB paid out £179,000 to solicitors in relation to 429 cases submitted for payment. The average case cost under the category of ‘housing/recovery of heritable property’ was £599, inclusive of fees paid to advocates and solicitor advocates. The average case cost under ‘advice and assistance for recovery of heritable property’ cases was £249.

Rates of pay

Since April 2023 solicitors doing this work are paid at £63.88 per hour under ‘advice and assistance’. This is a 25% increase on the £51 per hour that solicitors were paid for this work before April 2019. Short letters of a formal nature and telephone calls of up to four minutes are charged at £3.64. Longer letters and phone calls lasting between four and 10 minutes are charged at £9.10.

Civil legal aid in an eviction case is paid on a block fee basis. A defender’s solicitor is paid £101.58 for all work ‘from taking instructions (including instructions for a counter-claim) up to and including lodging the form of response’. The fee for preparing for the first diet of proof is £110.08, which is reduced to £91.70 should the proof settle seven or more days before the proof diet. Preparation for any adjourned diet of proof is £55.05. The fee for appearing at a continued first calling is £26.44 per half hour. Those doing this type of work will know that continued hearings are common.

Housing solicitors will also be aware that there exist numerous possible defences to an eviction action, from challenges to the competency of the case, to reasonableness defences and public law defences under the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) and Equality Act 2010, to name a few. Proper inquiry into those defences, evidencing them and then drafting defences is likely to take several hours yet is paid at £101.58.

Complex work

Wheatley Homes Limited v Shariff 2025 SLT (Sh Ct) 56 is a recent sheriff court case where both the Equality Act and ECHR were relied upon by the defender. It is a good example of how complex these cases can be. It is only because the defender was eligible for legal aid that she was able to access specialist legal advice from a charity, instruct expert witnesses and ultimately counsel. She was successful in her defence. This is the first reported Scottish decision concerning the application of Section 15 of the Equality Act, 10 years after the landmark decision in Akerman-Livingstone v Aster Communities Ltd [2015] UKSC 15.

There is unmet legal need in the area of housing and homelessness. This article has focused on evictions, but the position with regards homeless people denied assistance from statutory homelessness services and others who have been trapped in damp and substandard housing is no better. With the above noted rates of pay it is hardly surprising that there aren’t more solicitors doing this work.

The true cost

Legal aid does not cover the true cost of doing this work, to the standard required and with the person-centred and trauma-informed approach we aspire to deliver. Most solicitors in Scotland who specialise in housing and homelessness law and are able to do volume-based work in this field are based in law centres and charities, where grants, charitable funds and donations subsidise the firm’s running costs.

Those law centres and charities cannot, however, match the solicitor salaries of the Civil Legal Assistance Office or most other law firms and public bodies. Increasing the current fee rates isn’t just a question of attracting new solicitors to legal aid; it is also a matter of ensuring that law centres and charities can retain their existing staff, who are overwhelmed by the volume of enquiries and, according to the preliminary data, only able to assist in a minority of eviction and repossession cases.

Written by Fiona McPhail, lecturer in social justice at the University of Glasgow and previously Principal Solicitor at Shelter Scotland.