Trusts and the family business

The English High Court case of Hughes v Bourne [2012] EWHC 2232 (Ch) (27 July 2012) is of interest to all private client lawyers, but should be of special interest to those advising family businesses. This article concentrates on the lessons for advisers to family businesses, rather than the technical legal issues which arose. Although the author is based in Scotland, the wider issues arise in almost every jurisdiction.

We know that there are three subsystems within the family enterprise – the family, the business and the owners. Within the ownership group there is also a potential balancing act where shares are held in a trust structure. The interests of trustees and beneficiaries can be very difficult to reconcile, especially in the family business context when the family, the business and the owners have varying and differing interests.

A trust is a tripartite relationship, involving a truster or settlor, trustees and beneficiaries. Trustees are subject to a restriction and legal obligation that the trust property passed to them must be used for the achievement of the aims of the settlor as set out in the trust deed, and for the benefit of the beneficiaries. The role of trustee can be a tricky one, especially if the trustees seek to make a decision based on solid financial principles but this does not meet the needs and interests of some or all of the beneficiaries. The trustees when exercising their fiduciary duties must not allow one beneficiary to suffer at the expense of a benefit to another beneficiary. Disputes between trustees and beneficiaries increasingly tend to be subject to litigation which is confrontational and likely to damage irrevocably the relationship between them. After litigation, whatever the outcome, it is unlikely that a relationship based on trust could ever be reinstated.

Background

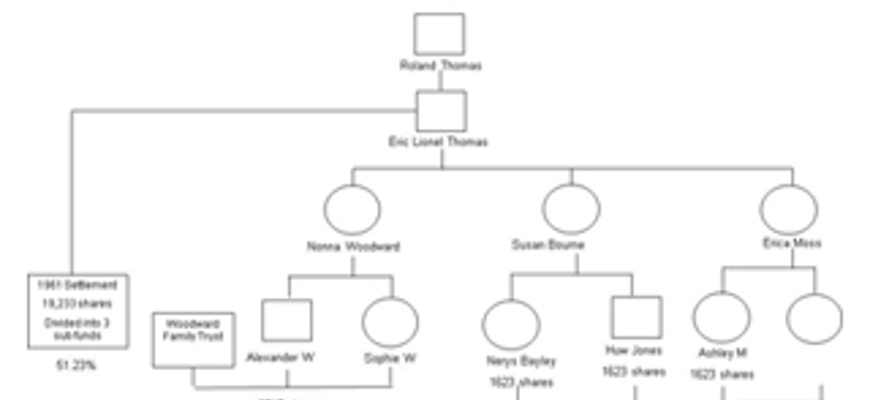

The case of Hughes was an application for direction by the trustees of a family discretionary trust (“the 1961 settlement”), the principal asset of which was a controlling shareholding (about 51%) in a local newspaper company which had at one point been owned by the father (Rowland Thomas) of the settlor (Eric Thomas). The trustees wished to accept “an exceptionally favourable offer” (in the words of Mr Justice Henderson) from a competitor newspaper business (of Sir Ray Tindle), but this would have meant selling the trust’s shares against the wishes of some of the beneficiaries, namely two branches of the family, the Bourne family and the Moss family. The offer was conditional upon Sir Ray acquiring at least 51% of the shares. The present shareholdings are set out in the ownership geneogram:

A crucial point in the case was the fact that, by deed of appointment in 1975, the then trustees of the 1961 settlement irrevocably appointed the future income from the whole trust property one third to each of the three daughters of the settlor, Mrs Bourne, Mrs Moss and Mrs Woodward, for their respective lives. An interest in one third of the whole is very different from an interest in a divided third of a fund. By further deeds of appointment in 1983 and 1984 and a deed of appropriation in 1993, the trustees appropriated one third of the shares to each of three sub-funds to be held in trust for the daughters’ respective children, subject to each of the settlor’s daughters’ life interests, and this was consented to by the trustees and by each daughter.

Because of the 1993 appropriation, the court held that beneficiaries of the Bourne and Moss sub-funds were entitled to direct the trustees how to deal with those shares. The beneficiaries were held to have no community of interest and this altered significantly the relations not only between all of the beneficiaries, but also between the beneficiaries in the sub-funds and the trustees.

The trustees clearly had a fiduciary duty to the beneficiaries of the trust and had “a strong desire to act in the best interests of all the beneficiaries” (in the words of Mr Whitehair, one of the trustees), considering all of the shares as a whole. However, because of the nature of the offer and the disagreement amongst the beneficiaries (and the trustees’ failure to take individual direction from each of the class of beneficiaries of the sub-funds on what they wished regarding the one-third shares in each fund), they sought court approval of their proposed course of action, which was to accept the offer.

Ultimately, the case failed because the court invoked the rule in Saunders v Vautier (1841) EWHC Ch J82; (1841) 4 Beav 115 8, entitling the Bourne and the Moss family to demand that the shares in their sub-funds were transferred to themselves. The trustees were thus unable to override the beneficiaries’ wishes. The provisions in the company’s articles of association, although complex, permitted such transfers.

This left the 1961 settlement with control of only 17.08% of the company shares and this, even when coupled with the Woodward family’s own shares, was insufficient to meet the 51% of the company shares upon which Sir Ray’s offer was dependent.

The trust route

The case obviously concerned an English trust, but the procedure would have been similar in Scotland and, no doubt, in many other countries. In Scotland, trustees with difficulties arising out of a particular set of circumstances can petition the Inner House of the Court of Session for directions, although the rule which was the basis of the decision in Hughes does not apply in Scotland and the decision here might well have been different.

The emphasis of this article is however on the lessons for family businesses, and there are important points to draw from this case.

The trust was established during the settlor’s lifetime. This can be a big advantage in enabling the controlling business owner to pass on his knowledge of the business and the dynamics of the family. But to whom?

The judgment did not consider why the settlor had refrained from passing the shares to the next generation directly, which of course could be for a number of important reasons such as the following:

- he might have considered that the next generation was not yet old or mature enough to own the shares in their own right;

- he may have wanted the trustees to act as custodians for future generations, with the family either having access only to the income from the trust, or an opportunity, but not entitlement, to be considered amongst a class of beneficiaries for distribution of income and capital;

- a wish to restrict ownership of at least some of the shares to family members who were or could in the future be involved in running the business;

- a belief that children should be treated fairly and equally, and that there is difficulty in maintaining financial equality and equilibrium within the family due to the nature of the asset, being the shares in the family business; or

- the motive might have been tax planning.

The reasons for setting up the trust were probably a combination of all of these.

Trustee issues

The important decision of who should be appointed as trustees was also considered, and the settlor appears to have chosen wisely. Mr Justice Henderson states: “The trustees bring a formidable combination of long experience and relevant business expertise to the discharge of their duties.” All three trustees had held office for between 20 and 25 years, with Mr W having been a chairman of the company since 1994 and having more than 30 years’ experience in the local media industry. Mr H was a close colleague of the settlor during his lifetime, and Mr Hughes had been a non-executive since 2004 with a background in banking and corporate.

One of the most important considerations in succession planning for a family business where a trust structure is favoured is the choice of trustees. Given that the trustees will be constrained by what they can and cannot do under the terms of the trust deed, and being mindful of the fiduciary duties of which they must take cognisance, the appointment of trustees with extensive experience in the role envisaged and of having worked with similarly situated families is a must. The settlor in this case had therefore chosen the trustees well.

One of the main difficulties which trustees face is the requirement to fulfil their fiduciary duties, being the obligation of a duty of care to the beneficiaries at all times. Any possible decision or action which might be contrary to the fiduciary duties must be expressly permitted by the trust deed and cannot be implied. However, whatever the trustees do or don’t do, it must not amount to gross negligence. Case law reiterates that there is an irrevocable core of obligations owed by the trustees to the beneficiaries which cannot be excluded in any way, even by the inclusion of trustees’ immunity clauses in the trust deed.

In the Scottish case of Clark v Clark’s Trustees 1925 SC 693, the truster (settlor) had stated that certain shares which he transferred to the trust should be retained and that the trustees would not be liable for any loss that might arise in respect of these during their retention. The shares were retained for a period of years and they depreciated in value and became worthless. The court held that by their failure to reconsider the policy of retaining the shares, the trustees had been guilty of negligence amounting to breach of trust; the trustees were therefore personally liable for the loss sustained and the immunity clause within the trust afforded them no protection.

Disgruntled beneficiaries are likely to seek recompense if the trust assets become worthless due to the trustees following the settlor’s wishes. Even if an absolute direction was made by the settlor in the trust deed that, for example, the shares in the family business were to be retained in trust, the trustees would nevertheless be under a duty to protect the trust’s assets on the basis that the settlor did not intend the loss of value to happen and their obligation is to seek to maximise the trust fund.

This could put the trustees in a very difficult position, even if the language in the trust deed is clear and unambiguous. Not only can trustees face conflict between following the settlor’s wishes on the one hand and maximising the trust fund in the interests of the beneficiaries on the other: there is the business itself to consider. By following the settlor’s direction to the letter, this could hinder the development of the family business if, for example, the trustees refrain from voting to approve a merger or joint venture that will further the strategic plan of the business.

Conflict of attitudes

It is clear in the Hughes case that the trustees had given a great deal of thought to the fact that “the newspaper industry is in decline with profits and turnover falling rapidly” (the prospective purchaser Sir Ray Tindle, quoted in the minutes of the trustees’ meeting held on 5 July 2012). The trustees clearly believed their hands were tied and they could not retain the family shares. This decision was however contrary to the view of a number of family members, who perhaps for emotional reasons did not wish to see the family legacy dissolve, or at least wanted to maintain a connection to the newspaper industry.

Problems such as the Hughes case are more likely to occur where the family business has not articulated its values and views. Hughes highlighted a clear conflict of two different attitudes to ownership – custodians (some family members) and value-out owners (other family members and the trustees). Trustees are more likely to think in the same way as an external investor, with the return on the investment being of paramount concern, especially given the rules and duties that they are constrained by. They will tend to be financially cautious and seek to maximise return. They may have an involvement in the company’s affairs especially if they hold a large number of shares, but they are unlikely to be influenced by sentiments such as family reputation, job security for employees, and a sense of duty to sustain a legacy that has been inherited.

In Hughes the potential conflict amongst the family was heightened by the fact that the competitor’s offer would only proceed if they acquired at least a 51% shareholding, and without at least 54% of the trustees’ total holding being sold, the offer would fall. The Woodward family members had their own holdings but they needed the trustees to collaborate.

The family business can face further difficulties where there has been fragmentation of ownership between different family branches and trusts which, when coupled with the lack of a stated mission, vision and values, can leave the business open to lack of direction and conflict. This was highlighted in Hughes, where the Woodward family wanted to sell but the Bourne and Moss families used their combined power to frustrate this.

Think governance

Through the passage of time the Thomas family had become more complex, moving from a controlling owner to a trust and a sibling partnership, and ultimately moving towards a cousin consortium. Family businesses require a formal governance structure in place to ensure that the business continues to run effectively after the original business owner’s departure. For example, ensuring that the family has articulated its own needs and objectives clearly in a family charter or constitution and, if necessary, forming a family assembly and council as a forum where the members of the family have an opportunity to be heard. This can allow the family to have an impact on policies which are important to the family and which can be brought to the attention of the owners and the business, thus making the running of the business more likely to be successful.

We are not advised why the shares were put into trust. We can imagine that it may have been the absence of suitable family members to accept the shares in the business, or being of an age that to do so would be unsafe. The discretionary trust structure is the best known and researched legal structure to accept the transfer of shares of a family business where direct transfer is ruled out. Transferring the shares during the controlling owner’s lifetime should have enabled both the controlling owner to pass on his wealth of experience and knowledge, but also the younger generation to be educated and trained under the support of the older generation or to serve as a trustee.

The trustees were chosen with relevant experience and expertise to enable them to discharge their duties. The late Eric Lionel Thomas (the settlor) did many things to help ensure his company’s future success; however, we can surmise that he did not give sufficient consideration to the governance structure of the business and the family to ensure that it was able to cope with the move from a controlling owner form to a form where some of the shares are owned in trust (with the trustees representing a significant portion of the family’s ownership interest), and some by a sibling partnership. By failing to appreciate the anxiety and tension which were likely to develop as the family grew up and grew apart, with the family ownership structure having moved to a cousin consortium and with no “glue” to hold the family together, the chances of a successful transition were marginal.

Fortunately, there is a growing band of lawyers and other professionals who understand that family enterprises are different and that those family businesses which are likely to survive the evolution of family succession will do so because they have become better organised and have a governance structure and strategy which is clear and unambiguous.

In this issue

- Players and winners

- Access to client money?

- Tax and residential property

- Trusts and the family business

- Planning: the next level

- Reading for pleasure

- Opinion: Tom Mullen/Alan Paterson

- Council profile

- Book reviews

- President's column

- Deed plan criteria

- Decision time for justice

- "Can do": can you?

- Taxes heading north

- When the agent answers

- Taking care of child cases

- Collective redress

- Making sense of hearsay rules

- Don't forget the register

- Alcohol: the healthy option

- Seeding scheme is a draw

- Scottish Solicitors' Discipline Tribunal

- Human trafficking: is the system responding?

- Power points and positive rights

- A way to apply yourself

- Society presents "ambitious plans"

- Law reform roundup

- Business benefits

- On the right track

- Ask Ash

- Business radar

- Legacies: the untapped potential

- Charity begins at law

- Love them and leave to them

- Those difficult relatives