Sorry: no longer the hardest word?

There has been much discussion in the media of apologies and the potential legal consequences of saying sorry, most recently Thomas Cook’s apology in May to the parents of two children who died of carbon monoxide poisoning at a holiday cottage in Corfu nine years ago. Fear of litigation is cited as a common reason for not apologising, which has in turn prompted a series of legislative proposals, including the Apologies (Scotland) Bill.

According to its policy memorandum, the bill is designed to “encourage a change in social and cultural attitudes towards apologising”. The Scottish Government believes that there “appears to be an entrenched culture in Scotland and elsewhere that offering an apology when something has gone wrong is perceived as a sign of weakness”. Perhaps more relevant to the current discussion is the observation that “there is also a fear that an

The bill aims to “create a less adversarial climate” that will lead to “a reduction in the number of potential pursuers inclined to litigate, where an effective/sufficient apology has been

In reality, the Apologies Bill (discussed further at Journal, September 2014, online exclusives), does little more than clarify the current position under Scots law – namely that an apology does not amount to an admission of liability in itself in civil proceedings. However, that such a bill is seen to be necessary highlights the fact that there are many misconceptions regarding the legal consequences of saying sorry. This is despite very clear advice to the contrary. For example, in its leaflet “Saying Sorry”, the NHS Litigation Authority stresses: “Saying sorry is not an admission of legal liability; it is the right thing to do.”

Candour: the next step

The Apologies Bill is not the only proposal being explored. Reassurance that an apology won’t get you into trouble is one thing. Requiring an apology when things go wrong is another thing entirely. This is where the duty of candour comes in.

Essentially, a duty of candour requires openness, honesty, and an apology when things go wrong. The duty can be split into an organisational and professional duty of candour. The professional duty of candour applies to medical professionals UK-wide. The organisational duty of candour now has a statutory footing in

Concerns over patient care and high mortality rates at Stafford Hospital in England brought the issue of candour to the fore. In

Essentially, this duty requires healthcare providers to notify patients and apologise when things go wrong: see reg 20 of the Health and Social Care Act 2008 (Regulated Activities) Regulations 2014.

As soon as reasonably practicable after becoming aware that a notifiable safety incident has occurred, organisations must tell the patient, in person, all known facts about the incident. They should let the patient know what further enquiries are appropriate. Finally, they must apologise. A written record of the notification should be kept. This should be followed up in writing, detailing the results of any further enquiries that are undertaken.

Patients need not be informed of a “near miss”, providing no harm has been done. A notifiable safety incident is defined as an unintended or unexpected incident that results

The Scottish bill

The Scottish proposals are relatively similar to the English legislation. The Health (Tobacco, Nicotine etc and Care) (Scotland) Bill would create a legal requirement for health and social care organisations to implement the duty of candour procedure when individuals have been harmed because of the care they have received.

The harm needs to be of a similar nature to a “notifiable safety incident” under the English legislation, and relate to an unintended or unexpected incident, rather than the patient’s illness or condition. Where such harm has occurred, the duty of candour procedure must be followed, which will be set out in regulations made under the bill. These may include provisions about the apology to be provided and the notification procedure, among other things. An apology will not in itself amount to an admission of negligence or breach of statutory duty.

Incidents must be recorded and monitored, and the regulations may encompass training and support for those carrying out the duty of candour procedure. The duty applies to health boards, NHS National Services Scotland, independent health care services, local authorities and other providers of care and social work.

Methods of ensuring compliance differ between the jurisdictions. In Scotland, the proposals allow specific healthcare regulators to serve a notice ordering organisations to produce information within a specified time frame. The regulators can then report on compliance with the duty. The sanctions for non-compliance are much more severe in England, where

Appropriate apology

Overall, the duty of candour and the requirement to apologise should be welcomed. The doctor-patient relationship depends on a solid foundation of trust. An Ipsos MORI poll last year found that 90% of respondents would trust doctors to tell the truth. Professor Norman Williams, President of the Royal College of Surgeons, and Sir David Dalton, chief executive of the Salford Royal NHS Foundation Trust, suggest in their review, Building a culture of candour, that this may be why individuals react so strongly when they feel that candour is lacking. With greater expectation comes a greater sense of disappointment when people are let down. The duty of candour can go a long way to reassuring patients and rebuilding trust.

What is notable in both the English legislation and the Scottish bill is the definition of apology as “an expression of sorrow or regret”. There can be no doubt that a sincere apology has many benefits. It is a vital part of the psychological healing process, not only for those who have been

In spite of this, the English legislation and the Scottish bill should hopefully put patients back at the heart of the process. Crucially, the Scottish policy memorandum states that the duty of candour procedure “will emphasise learning, change and improvement”. In accordance with those aims, the regulations may encompass training for staff, support for those affected by the harm, reviews of matters leading to the event, and reports on implementation of the duty.

As noted earlier, fear of litigation is cited as a common reason for failing to apologise. It remains to be seen whether the Scottish proposals will have an effect on levels of litigation. The Dalton-Williams review notes that while some acts of candour might lead to litigation, “the aggregate effect of greater candour on levels of litigation is unlikely to be significant”. It further states: “It seems likely that if organisations really put candour into practice, there will be real gains in preventing drawn-out cases where legal action is really an expression of the intensity of the desire to know what happened rather than an attempt to secure financial redress.”

Even if the duty does not lead to a reduction in litigation, perhaps it will lead to greater cooperation. Claimants may be more willing to negotiate with those who adopt an open and apologetic approach. In any event, as the Dalton-Williams review observes: “Fear of litigation is clearly not a principled argument against candour: something that is not in your interests can still be the right thing to do.”

We do not live in a perfect world, and things do go wrong. But when they do, patients and their relatives expect honesty. They expect doctors to tell them how any harm can be dealt with, and how similar incidents can be prevented in future.

In this issue

- Land registration and leases

- Disharmony and disharmonising

- FCA reviews: not the end of the story?

- A host of claims for guests

- Pensions auto-enrolment: some clarity for trainees

- Reading for pleasure

- Opinion: Stewart Cunningham and Nadine Stott

- Book reviews

- Profile

- President's column

- KIR: have your say

- People on the move

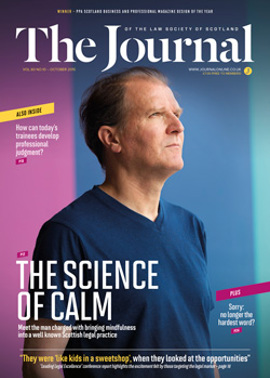

- You and whose mind?

- Deil tak the hindmost

- Cultivating judgment

- Women: paths to power

- Sorry: no longer the hardest word?

- Fairness in the balance

- Minimum pricing: the latest

- Planning: shakeup on the way?

- New burdens for employers?

- Scottish Solicitors Discipline Tribunal

- Ancillary rights as real rights

- Life at the cutting edge

- One form if firms hold client money

- Further fraud alerts issued

- Law reform roundup

- Guidance: duties re legal rights

- From the Brussels office

- Rights in chaos: asylum seekers and migrants in the EU

- Mirror wills: can I change?

- Renewal: the impetus for review

- Ask Ash

- The day of minimis is here

- If it ain't broken...?

- The voice of youth